It’s probably not a surprise to many of you that microgrids make a lot more sense than one big interconnected national grid.

We’ve been saying for decades that we need to move to distributed energy rather than relying on centralized control.

It turns out this would also be much easier for utilities to manage.

If grids were in chunks of 500-700 connections, they would be big enough to stabilize local fluctuations in power generation, but small enough to avoid large-scale failures, according to research by the American Institute of Physics.

In an enormous interconnected grid like ours, which has 16,000

connections, what starts as a small outage can quickly cascade through the grid. That’s what happened in the 2003 blackout when 50 million people were left without power.

"Sandpiles are stable until you get to a certain height. Then you add one more grain and the whole thing starts to avalanche. This is because the pile’s grains are already close to the critical angle where they will start rolling down the pile. All it takes is one grain to trigger a cascade," explains David Newman, a physicist at the University of Alaskahe.

"The problem is that grids run close to the edge of their capacity because of economic pressures. Electric companies want to maximize profits, so they don’t invest in more equipment than they need," he adds.

If just nine of the 30 key substations in the US go down on a scorching hot summer day, the entire grid could collapse, according to the Wall Street Journal, which reported on leaked excerpts from a Federal Energy Regulatory Commission report.

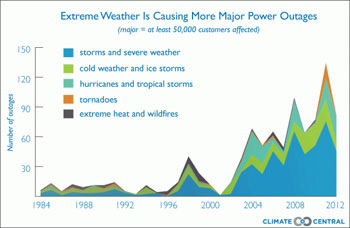

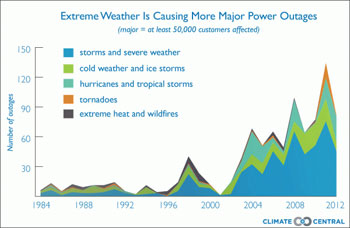

Indeed, weather-related blackouts have doubled over the past 10 years (those affecting more than 50,000 people) because of the increase in severe weather events, says Climate Central. There’s a 10-fold increase since the mid-1980s. Most have been caused by damage to large transmission lines or substations, as opposed to the smaller residential distribution network, they say.

Connecticut is the first to develop a state-wide microgrid and New Jersey is developing the first microgrid for a transit system. Sandia National Lab has designed microgrids that are running at more than 20 US military bases.

Learn more about extreme weather and the grid: